|

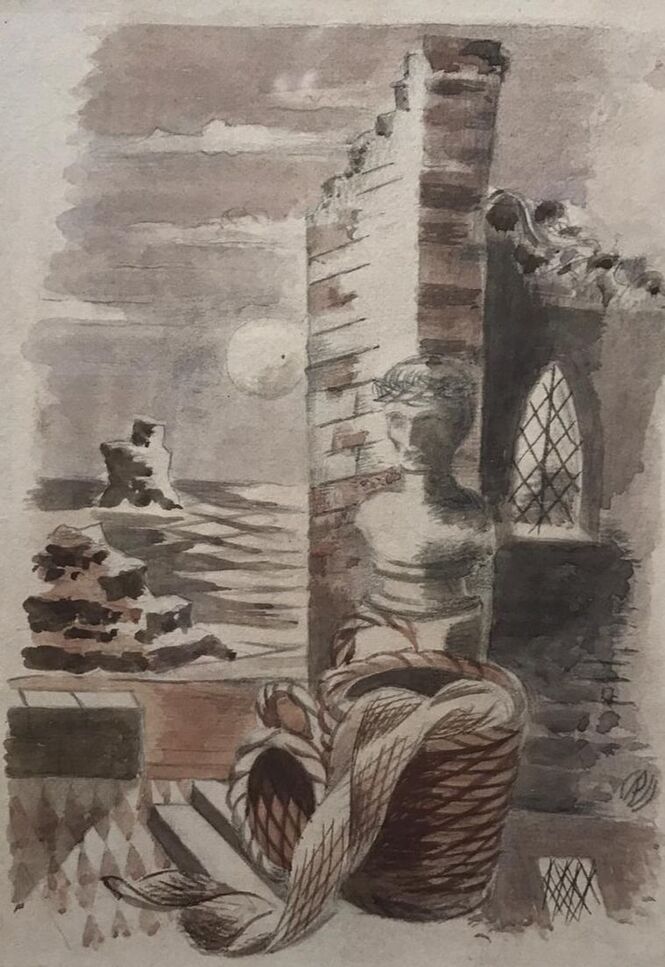

Paul Nash 1889-1946 The Garden of Cyrus - The Quincunx Artificially Considered 1931-2 Pencil and watercolour 21 x 15 cm Signed with monogram lower right PROVENANCE Ernest, Brown & Phillips, The Leicester Galleries, London (?) 1932; Redfern Gallery, where bought by Richard Smart; Private Collection. EXHIBITED Water-colour drawings by Paul Nash, Leicester Galleries, London, November, 1932; ?Watercolours and Drawings by Paul Nash, Frank Dobson, P.H. Jowett, Adrian Allinson, and Isabel Nicholas”, Redfern Gallery, London, February 1934. LITERATURE Andrew Causey, Paul Nash, Oxford 1980 pp. 221-34; Anthony Bertram, Paul Nash: The Portrait of an Artist, London 1955 pp.198-9; Andrew Causey, Paul Nash: Landscape and the Life of Objects, Farnham 2013 pp.86-97. This recently rediscovered work is a rare original watercolour for one of Paul Nash’s full-page illustrations for “Urne Buriall and the Garden of Cyrus”. In 1930 the Curwen Press approached Nash to illustrate a book of his own choosing. Nash selected the strange and idiosyncratic alchemical writings “Hydriotaphia, or Urne Buriall” and “The Garden of Cyrus” by Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682). These twinned treatises had first been published together in 1658. The project became Paul Nash’s magnum opus of 1930-1932. Nash produced fifteen full-page and seventeen half-page illustrations for the book, making original watercolours for each design. These all draw on numerous passages pulled from throughout Browne’s texts, but are stand-alone works in their own right. Nash seems to have selected where the illustrations would be located within the published book, depending on his sense of how they best cited, or alluded to, relevant passages. The text aids with the interpretation of Nash’s illustrations but is also, in turn, illuminated by them. From the watercolours Nash made conté chalk drawings for Curwen’s artists to use in the creation of the collotype plates. The collotypes were then hand-coloured through pouchoir (stencils) and the watercolours were then referred back to, to check with the accuracy of the plates. This painstaking technique was described by Paul Nash, with much admiration, in his 1932 volume “Room and Book”. Nash oversaw the whole project: in addition to the illustrations he even chose the typeface and designed the bindings. The final published book is considered to be one of the Curwen Press’s masterpieces and Herbert Read described Nash’s illustrations as “one of the loveliest achievements of contemporary English art.” (1) Nash’s earliest biographer, Anthony Bertram, cited the huge significance which the “Urne Buriall and The Garden of Cyrus” project had for the artist (2). The venture absorbed him, renewed his enthusiasm and unlocked his imagination. Fed by imagery from the original texts, the project forms a vital bridge between Nash’s understanding of British Romanticism and what became his own, very individual, interpretation of Surrealism. More recently, the late Andrew Causey proposed that the venture provides the literary origin for Nash’s “personal mythology” 3. Nash’s interpretation of Sir Thomas Browne’s text combines mystical concepts with visual observations of geometry in nature. Here the wall and the waves of “The Quincunx Artifically Considered” are reminiscent of Nash’s earlier Dymchurch work but they now take on a more dreamlike feeling. The ball-like sun/moon in the sky forms another connection between Nash’s earlier and later work. With its meditations on death and remembrance, archaeological remains and geometry in nature, Browne’s “Urne Buriall and The Garden of Cyrus” unite many of the themes which were most important to Nash. “Urne Buriall” provides “a discourse of the sepulchrall urnes lately found in Norfolk” and examines, through archaeological remains, how the dead should be commemorated by the living. In the second text, “The Garden of Cyrus”, a work of natural philosophy, Browne asserts how “nature Geometrizeth, and observeth order in all things” – a concept which was to have a great bearing in Nash’s founding of the British Modernist art group “Unit One” in 1933. Browne promotes the importance of the “quincunx” (a saltire shaped cross, made from five points, as on 5th face of a dice) and uses this device to provide evidence for Platonic form in art and nature: for Browne many things could be “mystically apprehended in the letter X”. Browne suggests that light enters the eye as “pryramidal rayes” through the retina before being interpreted within and therefore “all things are seen Quincuncially”. The very act of seeing, therefore, becomes evidence for the importance of the “quincunx”. The original 1658 frontispiece of “The Garden of Cyrus” was a geometric design made from a latticework of quincunx. Nash was also to use the quincunx design, overlaid with an urn, as the gilded detail on the front and back covers of the fine bindings of the book, first produced by Nevetts (and later by Sangorski & Sutcliffe). In this watercolour Nash makes numerus allusions to the original text. He uses the quincunx in the latticed window of the ruined building; in the shadow it casts upon the floor; in the wicker baskets and spilling-out nets (which actually represent “ the nets in the hands of the Retiarie gladiators” (styled on fisherman and who fought with nets, specifically mentioned in Chapter II of “The Garden of Cyrus”)); on the tiled floor and also in the reflection of the sun/moon in the waves (Browne pronounces in Chapter IV of his work how the quincunx is “observable in the Sun and moon beheld in water”). The presence of the bust suggests the antiquity of these philosophical ideas. Whether the bust represents Alexander or possibly Cyrus the Great (whom Browne cites as the archetypal “wise ruler” and as “nobly beautifying the hanging Gardens of Babylon”) is a matter of conjecture, but the wreath on the head of this statue is also formed from conjoined quincunx (a detail which also picks up on another reference from Browne’s text where he develops ideas on ancient “diadems ... and handsome ligatures, about the heads of Princes”). The bust, however, also suggests an affinity between Nash’s work and the early “Metaphysical Paintings” of Giorgio de Chirico, Alberto Savinio and Carlo Carrà (de Chirico, had held his first London exhibition at Arthur Tooth & Sons in October 1928). There are minor differences between this original painterly watercolour and the more graphic illustration of the published collotypes. Here the socle beneath the classical bust is slightly broader; the stones of the ruin are better defined; the waves are rolling slightly more naturally; the lattice shadow of the leaded window is more criss-crossed and there is a lighter, painterly touch to the tiled floor etc. Other important works from Nash’s scheme for “Urne Buriall and The Garden of Cyrus” which contain “geometry” include “The Soul Visiting the Mansions of the Dead” with its shelf-like structure (The original watercolour for that work is in the collection of the British Council, a later and larger worked-up version is in Tate). Five watercolours and three oils were enlarged by Nash between 1932 and 1933. In 1933, in the light of the work he had undertaken on “Urne-Buriall and The Garden of Cyrus”, Nash visited Silbury Hill and Avebury for the first time. The ideas he had whilst occupying himself with Browne’s mystical writings, combined with this trip to ancient Wiltshire sites to provide the seminal inspiration for a new period of artistic output. Geometry and the quincunx resonate throughout his subsequent work: in the 1935 painting “Equivalents for the Megaliths” (Tate) a landscape of ancient earthworkings is juxtaposed with a series of abstract forms. A conventional perspective, enhanced by Nash’s observation of the man-made criss-cross patterns within the field of stubble, is set against a white upright grid. The circular face of the principal object on the right hand side of the composition is marked prominently with a red quincunx. Richard ‘Dick’ Smart, the first owner this watercolour, was a director of Arthur Tooth & Sons. An Australian from Adelaide by birth, he was London buyer for the National Art Gallery of South Australia. He represented a number of highly regarded contemporary British artists and, in due course, became Paul Nash’s agent. He acquired a number of important works by the artist. After Nash’s death, Dick Smart was a crucial correspondent with his widow, Margaret Nash, and helped her with the handling of the artist’s estate. Notes: 1. Herbert Read, “Philosophy of Modern Art”, Faber & Faber, London, 1952, p. 180. 2. Anthony Bertram, “Paul Nash: The Portrait of an Artist”, Faber & Faber, London, 1955, pp.27 3. For an examination of this project see pp. 221-234 Andrew Causey “Paul Nash” Oxford, 1980 4. Cited in Causey, Nash, p. 222 5. See Tate 1975 Catalogue entries 139-143 on pp 81-82 of “Paul Nash: Paintings & Watercolours” |

Proudly powered by Weebly